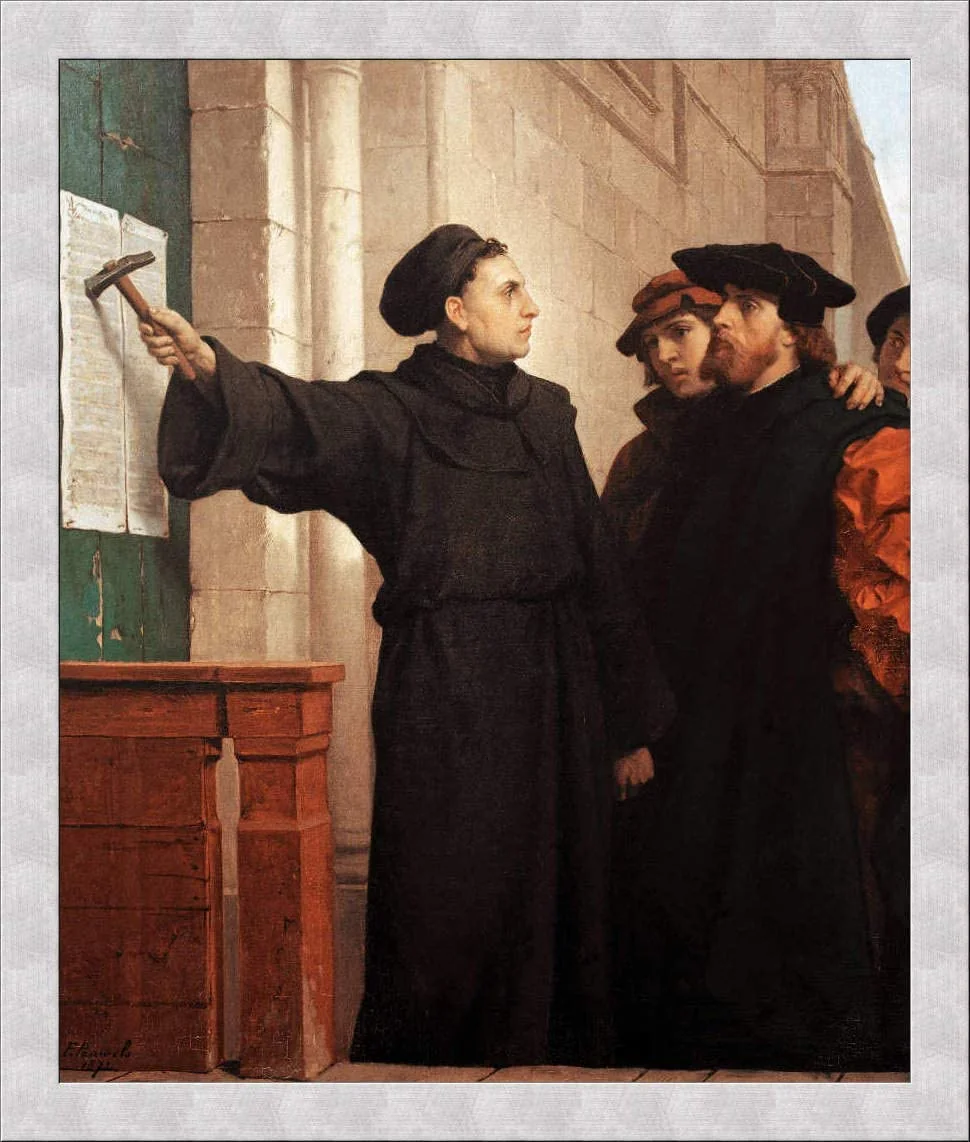

The 16th century was a turbulent time in Europe, a time that would see Europe move out of the background and into the spotlight of global politics and economics. Front and center of that change was the Protestant Reformation of 1517. On a cool morning in October 1517, Martin Luther, a teacher and monk, published "Disputation on the Power of Indulgences" otherwise known as the 95 Theses. The 95 Theses, famously nailed to a castle church door in Wittenberg, presented 95 ideas about Christianity, 95 ideas that directly contradicted the teachings of the Catholic Church. Martin Luther was not the first to question the ethics of the Catholic Church, the early 1500s saw a sharp increase in criticisms against the Catholic Church and branched-off protestant religions and ideas. One has to wonder why Protestantism became such a large movement in the 1500s specifically, why not earlier, and what else was happening in Europe and beyond at the time.

To answer this question, let’s backtrack to the time of the Crusades and the Knights Templar. Most people are familiar with the Crusades and the Knights Templar, recalling stories of their armies protecting Catholic pilgrimage to the Holy Land in Jerusalem, dawning a white cloak bearing a red cross, defending Europe against the rising tide of Islam, and so on. The Knights Templar and the Crusades have a questionable history at best, however, our focus is on the rise of Protestantism a few hundred years later. On that note, why talk about the Knights Templar at all? Because the Knights Templar were not singularly motivated by a desire to spread Christianity and stop Islamic expansion into Europe, the Order of Knights, the Pope, and the rulers of Europe at the time had a financial desire to reach Asia as well. In the 12th century, Europe was completely blocked from reaching the rich countries of Asia by what we now call the Middle East/ West Asia completely blocked all trading from Europe into Asia. The clear religious divide between Catholic Europe and the Islamic Middle East certainly caused tensions, but I’d argue that the underlying motivation for the Crusades was one of financial gain, religion was simply a convenient scapegoat. More on this when we return to the rise of Protestantism.

The Knights Templar was established in 1118 AD by Frenchman Hughes de Payens and received Papal recognition in 1128 AD under Pope Honorius II (r. 1124-1130). Their self-stated mission was to aid and defend Christians on their pilgrimage to the Holy Land. It was initially a small order of 9 men but after Papal recognition, noblemen from across Europe joined their ranks, increasing their membership and influence. One of the most influential contributions of the Knights Templar, in my opinion, was the establishment of what we today might call “traveler’s checks”. Journeying from Europe to Jerusalem was a long and arduous journey, pilgrims generally had to travel with a lot of money on hand to support their journey to the Holy Land and back, making them prime targets for robbery. The Knights Templar begat a system wherein a traveler could deposit their money at a Knights Templar office, and they would issue them a document stating how much they deposited, along the route to Jerusalem, travelers could stop at any office and withdraw money, and they would be reissued a document stating how much they had left in their account. This was a very efficient and very profitable venture for the Knights Templar, and this enabled the organization to further invest in revenue-producing properties such as farms, vineyards, churches, etc.

By the 13th century, the Knights Templar ran such profitable banks that kings of France and other European nobility entrusted their treasuries to the Knights Templar, and the organization even lent money to rulers, a function that may have eventually led to their bloody disbandment. The following 2 centuries of failed crusades led to a disillusionment with the Order, their popularity was failing, access to the Holy Land was becoming increasingly inaccessible, and their success as a bank and money lenders was prompting resentment from nobility who were in debt and either refused loans or nobles who were unable to pay back old loans. French King, Louis IV, with the support of Pope Clement IV, dissolved the Order in 1312 AD. However, this was not the end of their story. Under a new name, Ordo Militae Jesu Christi, the Military Order of Christ, was established in Spain and Portugal in 1319 by Pope John XXII and King Dinis of Portugal.

Why did King Denis want to reestablish the Order in Spain and Portugal and why would the Pope allow them to function exclusively in this region? The area of modern-day Spain and Portugal was still under Arabic rule and had been since 711 AD when Arab-Berber forces conquered the Iberian peninsula. The Islamic stronghold over the region extended from the coast right up to the Pyrenees mountains, a geographical feature that the Islamic forces were never able to conquer. The Pyrenees Mountains remained a stronghold for Christian European kingdoms and was the base from which they launched centuries of battles against the Islamic rulers, a group of battles referred to as the Reconquista. Absolving the defunct Knights Templar into the new Military Order of Christ, gave rise to a new wave of crusades against the Caliphate of Cordoba.

The legacy of the Knights Templar, reflected in the Military order of Christ, was the development of the “warrior-monk” figure, a group of people adept in warfare, commerce, finance, industry, and construction. The culmination of the traits established by the Knights Templar and the Military Order of Christ can be seen no clearer than in Henry the Navigator (1394-1460), son of Portuguese King John I and Phillippa of Lancaster. After capturing Ceuta, bordering the Straight of Gibraltar on the northern tip of Africa, in 1415, he set up a base of operations in Sangrees, Portugal, on the Northern side of the Straight of Gibraltar. In 1420, Henry was named the Grand Master of the Order of Christ. With his political ties to nobility and his access and control over the military and financial resources of the Order, he set his goals on finding a sea route to Asia, as centuries of crusades had failed. He also utilized the technological advancements of the Muslims, as the Caliphate in Spain, Northern Africa, and West Asia, was far superior in terms of science, math, and technology to any country in Europe to this point. Henry the Navigator brought together the best and brightest minds in science and navigation, leading innovations such as the caravel ship, and carracks, ships capable of sailing long-distance ocean voyages. He dedicated his life to navigating the Atlantic, hoping to find a sea route to Asia. He died in 1460 before realizing his dream but did make significant headway into navigating the western coast of Africa. The dream of reaching Asia was not too far away as Portuguese sailor Bartolomeu Dias reached the Cape of Good Hope in 1887, and Vasco de Gama reached India in 1498.

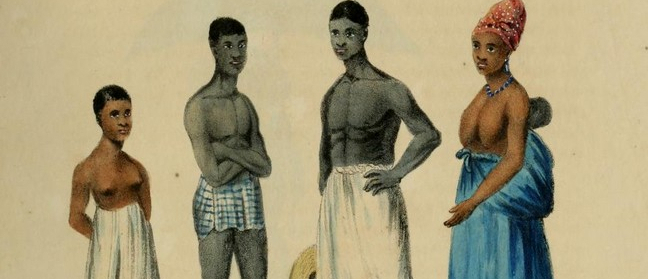

In 1492, Columbus, working for Spain, reached the Americas and in 1498, Vasco de Gama reached Asia when he landed in southern India. How can simply finding a route to the Americas and Asia impact Europe so much that its entire religious and political landscape has changed by the 1517 reformation? In the figure of the Knights Templar and Henry the Navigator, we see the beginnings of economics and warfare being interwoven into the fabric of the European rise to power. When Vasco de Gama reached Calicut, India in 1498, de Gama vastly misunderstood the trade dynamics between the various powers trading in and out of India at the time. He first arrived in India with a ship full of Portuguese goods to trade but no trader wanted them, he had to practically give them away, but he did secure a haul of Asian goods to return to Portugal that netted 60x the profit that the initial venture cost. This solidified Portugal’s mission to secure a trade relationship with India. In 1502, de Gama returned to India but was significantly more prepared, not with goods and gold but with warships and soldiers. Upon his return, de Gama demanded that the Indian ruler of Kozhikode cut off all trade with Arab merchants. This ridiculous demand was, of course, laughed at by the Zamorin (title for a ruler in Kozhikode), but de Gama did not accept no for an answer. He went on to attack and terrorize the coastline of India and while this specific attack did not immediately bring India or the Indian Ocean under the full control of the Portuguese, it did pave the way for further military aggression in the region.

Within a decade, Portugal had claimed victory over the region, not by waging a long and costly war on land or by forcing the countries surrounding the Indian Ocean into trade agreements, but by absolutely terrorizing the Indian Ocean with their superior ships, built for commerce and naval warfare. Knowing that the Portuguese were patrolling the ocean from the coast of West India, the Malacca Straight, and the Persian Gulf, the Portuguese had become the scourge of the Indian Ocean. The message came loud and clear the Indian and Arab traders, either trade with the Portuguese or face them on the terf they know best, the open sea. And the same groundwork for colonization was occurring in the Americas under Spain at the same time. Within 25 years of discovering these sea routes, Spain and Portugal had become the richest countries in Europe. Not only did they benefit from being the first European countries to discover these routes, but they also had the added benefit of the Pope “Splitting the world in 2” between Spain and Portugal, with Spain receiving the Americas and Portugal receiving Asia.

Martin Luther was born at a perfect cultural moment to both develop anti-Catholic sentiments and for those beliefs to burn through Europe like wildfire. In 1943, 1 year after Columbus discovered the Americas, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain enlisted help from Pope Alexander VI to ward off any claims on the newly discovered land from other countries. In a fortunate stroke of luck, Pope Alexander VI was Spanish-born and accommodated this request by splitting lands west of the Cape Verde Islands for Spain and East of the Islands for Portugal (this line changed slightly over the next decade but the principle remained the same). No other European powers ever accepted this Papal decree and it’s easy to understand why: Portugal and Spain were given an extraordinary scope of power and influence by the highest religious and political figure in Europe, the Pope. Would any good Catholic nation dare go against the Pope, even when they have been completely left out of the deal of a lifetime?

Here we return to Martin Luther’s 95 These, while they did not discuss the particular issue of trade routes or what have you, the effects of his work did have an immediate effect on the political climate of the time, one that was so pronouncedly felt that Martin Luther later wrote:

“If I, Dr. Martin Luther, had never taught or done anything else than to illuminate secular government or authority and make it attractive, for this one deed the rulers should thank me. . . . Since the Apostles’ time no theologian or jurist has more splendidly and clearly confirmed, instructed, and comforted the temporal rulers than I, by special divine grace, was able to do”

With Martin Luther, there came to be a clearer divide between the “word”, the relationship between Christ and Christians, and the “world”, which operated “through visible structures, published rules, and coercive force.” It is evident that Luther himself even understood that his Theses and criticisms of the Catholic Church enabled governments who felt maligned by the Church, to use the blossoming Protestant movement to fully separate from the Church to affirm their ambitions under a new secular, nation-state model of politics. Newly protestant countries were able to divert funds, land, and capital that previously were allocated to religious functions like paying dues to the Church or funding Catholic public works, could now be allocated to projects that benefitted the economic and commercial interests of the nation-state.

It’s evident that the driving motivator for warfare in Europe switched from religion to economics in the 1500s but it’s immediately evident why this occurred at all. I believe, as Martin Luther believed, that the rulers of Europe should thank him for illuminating secular government or authority and making it an attractive option against the monopoly of the Catholic Church. The swift and monumental influx of wealth and power into Europe was bound to shake up the social order, at the time, there was no obvious ascendant to the throne of what would become the European colonial era. From the onset, Portugal and Spain had a clear advantage, they inherited the mercantile and navigational expertise from the Arab rulers of the peninsula, and warfare and banking know-how from their integration of the Knights Templar into their base of knowledge and power. Being fervently Catholic nations, the added affirmation and power granted by the Pope only solidified their “rights” to all the wealth and power the “new world” afforded them. However, it’s only through hindsight that we know that the British ultimately won the “game.” Had the British and the Dutch not switched to Protestant religions, history as we know it may have been fundamentally different.

.png)

.png)