The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade was a dark time in human history. For over 3 centuries, millions of African men, women, and children were brutally taken from their homes of origin to serve as slaves in European colonies across the world. Once free men, these captured African people were shackled together, forced on ships, and sent off to wherever their enslavers thought they would make the most profit. It was not until 1807 that the British government formally abolished the slave trade within the British Empire. However, the story does not end here, by the time the slave trade was “abolished”, colonists throughout the world had become addicted to slave labor, their settlements depended on that free manpower and that dynamic would not change overnight nor would it change willingly. While the British were not the first empire to formally abolish the slave trade, they were the empire with enough global influence and naval maritime power to actually enforce this law. Although the passage of this law appears, at face value, to be a victory for human rights, the enforcement and application of this law prove otherwise.

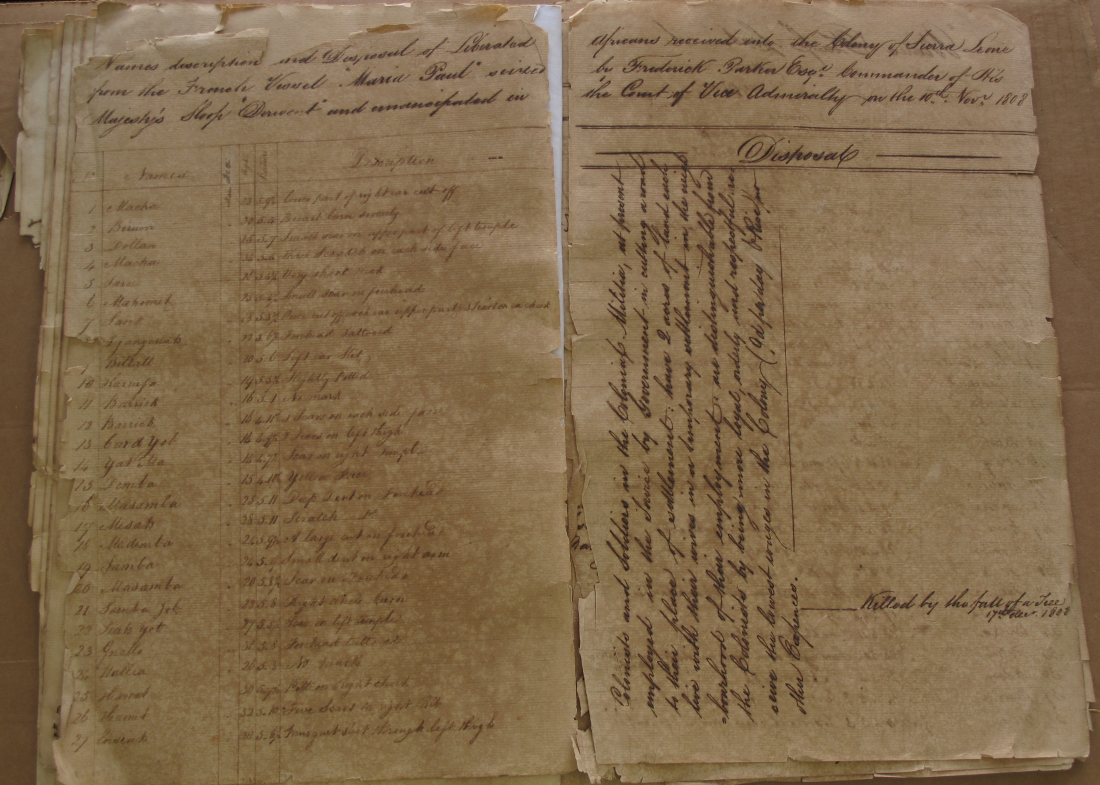

When the bill was passed in 1807, all slave ships leaving Africa were required to return to port and cataloged as “Liberated Africans”, however, “Liberated” is a bit of a double-edged sword. While the Africans on these boats were not sold into chattel slavery as originally planned, they were forced into involuntary indentured servitude. Indentured Servitude is when a person is forced to work under threat of legal or physical punishment. Although the African captives on these ships were not going to be forced in chattel slavery, they would have to hold a position as an indentured servant for a term of 3-14 years on average. These so-called “liberated Africans” were then taken to the nearest colonialist court and then added to a leger, that recorded their name, age, sex, height, distinguishing marks and physical features, date of arrival, ship of arrival, and the names of whomever they were to complete their involuntary indentured servitude to.

The slave trade spanned 350 years, starting in approximately 1526 and continuing until 1876. While the British abolished the slave trade in 1807, it carried on in various capacities for an additional 69 years, however, the anti-slavery, anti-slave trade movements gained increasing traction from the late 1700s until the formal abolition of slavery throughout the Western world in 1876. In 1787, two notable, British, anti-slave trade abolitionists Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. They believed that the abolition of the slave trade was the first step to abolishing slavery completely. While Clarkson and Granville set the stage for the British abolition of the slave trade, Denmark became the first European monarchy to abolish the slave trade in 1792 by royal decree Working with William Wilberforce, the leading voice of the abolitionist movement in parliament at the time, the British government successfully passed the Act of Parliament to Abolish the British Slave Trade act on March 25th, 1807.

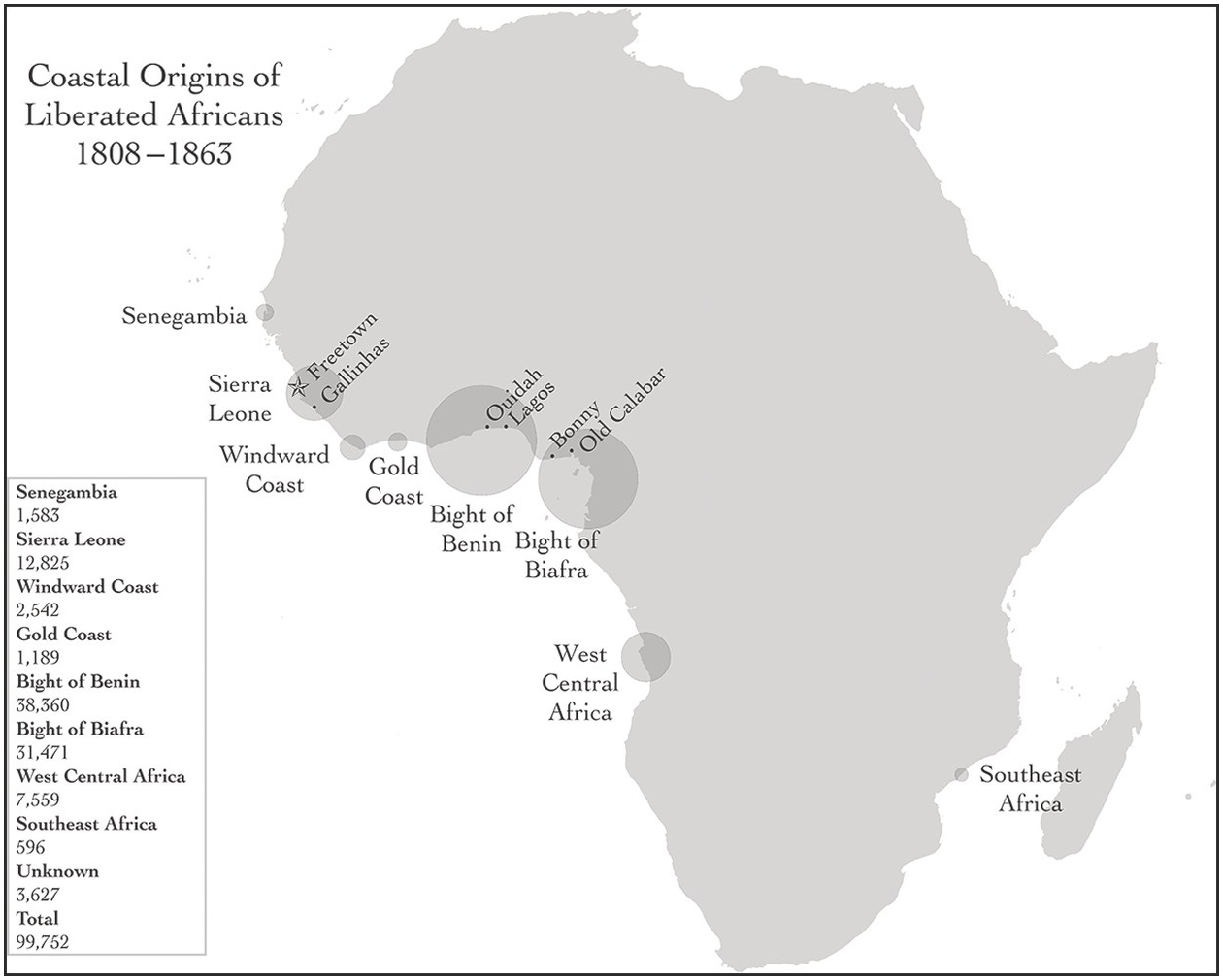

One important caveat of this act is that the slaves were not free simply by being intercepted by a British naval patrol, once the slaves were brought to the nearest Vice-Admiralty court, they were bought by the British government and then “freed” into indentured servitude to pay off their “debts”. From 1807 to 1815, British naval patrol units would classify slave ships as wartime enemies. It wasn’t until 1815 that Britain signed a set of bilateral treaties with Portugal, Spain, and the Netherlands that agreed to a set of internationally agreed-on policy for how to handle the re-acquisition and deportation of liberated Africans. The result of this was the establishment of international jurisdiction points for processing recaptive slaves. While these treaties grew to include more countries over the years and broadened the scope of slave ship retrieval, some countries, like the United States and France, continued to fight for and defend the institution of slavery well into the 1850s.

“Liberated Africans” became a legal status in which they could claim certain rights like fair wages or fair treatment but they were by no means entitled to it, which put them in a better legal position than chattel slaves who were solely viewed as property with no rights whatsoever, but still did not classify them as citizens with any guaranteed rights under any laws. A key tenant of the 1807 act was that these “liberated Africans” would be apprenticed during their tenured indentured servitude, an idea that was introduced by Granville Sharp, the British abolitionist who spearheaded the 1807 act. As is the case with many aspects of the long and drawn-out “end” of the slave trade, the well-intentioned idea of apprenticeship was perverted to create a new form of slavery. This system perpetuated the idea that these kidnapped Africans needed guardianship and help to integrate into British colonial society, that they had to be held by the hand to become “civilized”, this infantilization and paternalist mindset underpins the justification for colonialism and the institution of slavery.

The practice of apprenticeship is most notably seen in the colonies in Sierra Leone, as they were the first to implement it and did so at higher rates than other ports of delivery. Apprenticeship served a two-fold function: to teach a functional trade skill and to socialize these “liberated Africans” to British social customs. One important thing to note is that by the time the 1807 act was passed, the selling of child labor was at a peak high for the slave trade, meaning that apprenticeship became an issue of not just an issue of neo-slavery, but also one of child labor. Interestingly, the British-appointed governor, Thomas Thompson who was sent to the Sierra Leone colony in 1808, believed the apprenticeship system to be slavery under a new name. He launched a public investigation and found the practice to be abhorrent and banned the apprenticeship system in Sierra Leone that very year. This was a nasty public embarrassment for the British government and Thompson was replaced soon after by a governor that the crown saw as “more amenable” to the needs of the colony. Unfortunately, Thompson, who had the authority and wherewithal to advocate for these liberated Africans was disposed of before he could affect true change.

There are many lessons to be learned in the history of the liberated Africans, first and foremost being that there was no clean-cut end to slavery. It’s easy to point at the signing of a bill or the passage of an act and say “This year was the end of slavery”, but the truth is never so simple. Modern governments do not want to truly address how many concessions slave owners were given, how many sneaky ways they tried to reinstitute slavery, and how often governing bodies let slavery slide under the radar for so long with no consequences because no one wants to think of themselves as the villains in their own story. “Slavery was so long ago, we’re not like that now”, “It was a different time” are some common go-to phrases, however, as seen with the liberated Africans, the end of slavery really was just slavery by a different name. While there was some progress, like the recaptured slaves having an involuntary indentured servitude period of 7-14 years max instead of a lifetime of slavery as was the case with chattel slaves, it was still slavery. Liberated Africans were still infantilized, treated as lesser beings, and not given the same rights as their captors. They were still violently taken from their homes, forced to integrate and adopt a new language and a new culture, forced into trades and lives they did not choose willingly, and completely isolated from a life they once knew. The story of the liberated Africans will forever walk the paradoxical line of being the first step in a long fight for freedom and being victims in one of the longest and largest crimes against humanity that the world has ever witnessed.

.png)

.png)